Title IX of the Education Amendments of 19721 established the federal government’s commitment to equal access to educational experiences without regard to gender. Since its enactment, Title IX has been publicly recognized as providing women access into areas of college athletics and academics previously dominated by men. The number of women earning college degrees and entering into professional specialties—including medicine—has grown exponentially over the last 30 years. Before 1972, 9% of medical degrees were conferred upon women. In 2001, women constituted 44% of medical school enrollment and received 38% of medical degrees.2

Both the U.S. Supreme Court and the Office of Civil Rights of the United States Department of Education (OCR) recognize that sexual harassment can interfere with a student’s education and therefore constitute the discrimination prohibited by Title IX.3–5 The Supreme Court issued two decisions in the late 1990s holding educational institutions liable for monetary damages to students because of sexual harassment claims brought under Title IX.4,5 Although neither case involved medical education specifically, the Supreme Court had previously applied Title IX to a case involving the University of Chicago Medical School,6 and the Federal Courts of Appeals had applied similar principles to a school of dentistry7 and a medical school’s residency training program.8 In 2001, the OCR released a new guidance clarifying the principles that a school must use to prevent and eliminate sexual harassment as a condition of its receipt of federal funding in light of the Supreme Court rulings.

Under these new regulations, medical schools that receive federal funding have an affirmative legal obligation to address and prevent sexual harassment and abuse of their medical students and residents.3 Failure to comply with the regulations exposes the school to both a loss of federal funding and a suit for damages by an aggrieved student.

In this article, we will

- outline the extent of sexual abuse and harassment as revealed in recent literature and surveys;

- discuss the legal context for medical school liability for violations of Title IX under the OCR guidelines; and

- present an approach for medical schools to address sexual harassment that meets both the standards of Title IX and the underlying fiduciary responsibility to the students, the profession, and the public.

Sexual Harassment in Medical Education

Inappropriate sex-based behaviors in medical education have been documented in the medical literature. One woman physician reported on the sexist questions asked during her medical school interview: “Suppose that you meet the man of your dreams. He’s a banker who always arrives home at five o’clock. He wants you home at that time too. What will you do?”9 Often, medical lectures and rounds have been the forum for a sexist joke, a sexual comment, sexist teaching material, or the display of sexist pictures or posters.10 Individually directed sexual harassment behaviors in medical education include offensive body language, flirtation, unwelcome comments on the student’s dress, and suggestions to dress in a gender-appropriate fashion; also, outright sexual invitations, propositions, sexual contact, sexual bribery, and sexual assault have occurred.11 Exclusion from educational opportunities on the basis of gender, as well as discriminatory grading, have also been reported.12

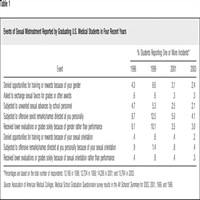

Since 1978, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) has administered an annual questionnaire to graduating U.S. medical students. In 2003, nearly 14,000 students were surveyed on a variety of topics, including their educational experiences, student support programs, and personal experiences of mistreatment.13 The 2003 survey results indicate that 15% of graduating U.S. medical students reported experiences of mistreatment during their medical school career. Four percent reported at least one experience in which an offensive sexist remark or name was directed at them personally, and 2% reported experiencing at least one unwanted sexual advance from school personnel. Nearly 3% of students reported experiences of discrimination in the form of poor evaluations and denied training opportunities that were based solely on gender rather than performance. The most common perpetrators of this mistreatment were, in order of frequency, residents and clinical faculty at the hospitals, nurses, patients, and fellow students.13 Our concern is that the negative effects of an incident of sexual harassment are not restricted to the individual student involved; seemingly isolated incidents may give rise to a hostile learning environment, affecting an even greater number of students. Despite increasing discourse on the problem of mistreatment in medical schools, the reported prevalence rates for sexual mistreatment have shown little improvement over the past seven years.14Table 1 shows the reported experience of sexual mistreatment among graduating U.S. medical students in 1996, 1999, 2001, and 2003.

Although the reported prevalence of sexual mistreatment in the AAMC survey is somewhat low, other data indicate that a higher number of students are sexually harassed in medical education programs. In a study by Lubitz and Nguyen,15 more than 21% of the male respondents and 64.3% of the female respondents reported “sexual abuse” during their third year of medical training. Most students reported that this abuse negatively affected their self-confidence, self-esteem, ability to learn, and their ability to provide good patient care.

In a study of sexual harassment during internship, Richman et al.16 reported on a cohort of students graduating from a state medical college. At the end of their internship, 11.3% of the men and 35.1% of the women reported experiencing a persistent pattern of “unwanted sexual advances” during their first year of training.

Although incidents of abuse are relatively common, complaints to authorities are rare. Cook et al.12 reported on the responses of medical residents to sexual harassment and abuse. Half of the residents discussed the issue or event with friends or family, but only about 18% discussed the event with a supervising physician. None reported the event to a sexual harassment officer or administrator, stating that they did not think it was a problem; that it was too minor to worry about; that reporting would not accomplish anything or was more trouble than it was worth; or that they had dealt with the problem directly. Respondents also feared that reporting might adversely affect their evaluation, cause them to be labeled, compromise confidentiality, or result in retribution or punishment.12

Because sexual harassment hurts students personally and impairs their performance, it also negatively affects the medical profession as a whole. Women students report feeling angry, afraid, demeaned, perplexed, guilty, or flattered while experiencing sexual harassment.16 Women who have experienced coercive sexual harassment report feeling a loss of personal autonomy and control, humiliation, shame, guilt, anger, and alienation as a result of the harassment.17 Physicians who recalled experiences of sexual harassment as medical students report diminished interest in their studies, as well as intrusive memories and depression.18 Of those suffering the most severe abuse, 28.8% considered quitting their medical studies completely.18

In a study of women physicians, Frank et al.19 found that there may be a relationship between harassment experiences and professional and personal dissatisfactions. Women physicians who reported a history of depression or suicide attempts were more likely to report previous experiences in medical training of sexual or gender-based harassment. Women with lower career satisfaction were also found more likely to report previous experiences of harassment during medical training.19

These studies illustrate the impact of sexual harassment on students, but only suggest the potential consequences on patient care. Medical educators are responsible for the development of professional attitudes and behaviors in their trainees, just as they are for advancing students’ medical knowledge and skills. Any tolerance of sexual harassment during medical training may perpetuate sexism within the profession and will likely produce a future generation of physicians that includes a significant number who treat both their colleagues and patients with disrespect.

Liability Issues of Sexual Harassment in Medical Education

The Revised Sexual Harassment Guidelines

The OCR’s 2001 guidelines define two types of sexual harassment in education: “Quid pro quo” and “hostile environment.”3 Quid pro quo sexual harassment occurs when a school employee or agent explicitly or implicitly conditions a student’s participation in an educational program or activity on the student’s submission to unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, or verbal, nonverbal, or physical conduct of a sexual nature.3 Hostile-environment sexual harassment occurs when unwelcome sexual conduct is sufficiently persistent, severe, or pervasive as (1) to limit a student or resident’s ability to participate in or benefit from an educational program or activity, or (2) to create a hostile or abusive educational environment. The behavior of “a school employee, another student, or a nonemployee third party” can create a hostile environment.3

Although quid pro quo sexual harassment can and does occur in medical education, this behavior is easier to identify as a violation of Title IX than the constellation of behaviors constituting hostile-environment sexual harassment. Quid pro quo sexual harassment is more episodic and may be dealt with effectively on a case-by-case basis. In this article, we focus primarily on the identification and prevention of hostile-environment sexual harassment; however the same principles apply to quid pro quo sexual harassment issues.

In evaluating claims of hostile environment sexual harassment, the OCR focuses on the issue of whether the “harassment rises to a level that it denies or limits a student’s ability to participate in or benefit from the school’s program based on sex.”3 The OCR will consider the degree to which the conduct affected one or more students, the type, frequency, and duration of the conduct, and the nature of the relationship between the agent and the student.3 Given the documented frequency of harassing behavior in medical education and the profound consequences of this behavior on students and faculty, we submit that medical schools should aim to achieve prevention, not just damage control.

Supreme Court Decisions

In the two Supreme Court cases mentioned at the beginning of this article, the court defined a school’s liability in private suits for monetary damages for sexual harassment. In Gebser v. Lago Vista Independent School District,4 the parents of a middle school student who had engaged in a sexual relationship with one of her teachers brought a suit for money damages against the school. No one had complained to the school officials about the teacher, but the family sought money damages from the school district after the relationship was discovered and terminated. The Supreme Court ruled that a school might be liable for monetary damages when a teacher sexually harasses a student, if

- an appropriate school official has actual knowledge of the harassment, and

- that official is deliberately indifferent in responding to the harassment.4

In 1999, the Supreme Court returned to the issue of pecuniary damages for violations of Title IX sexual harassment in the case of Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education.5 In this case, Aurelia Davis alleged that she was the victim of sexual harassment by a fellow student. The court held that a school also might be liable for monetary damages when student-on-student sexual harassment occurs in their education program, if

- an appropriate school official has actual knowledge of the harassment,

- that the official is deliberately indifferent in responding to the harassment, and

- that harassment is so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it can be said to deprive the victim of access to the educational opportunities or benefits provided by the school.5

In these decisions, the Supreme Court explicitly acknowledged the power of federal agencies to enforce regulations consistent with their mandate under Title IX, even in circumstances that would not give rise to a claim for money damages.4

Case Study

A medical student, whom we will refer to as Ms. A, described her experience during a third-year clerkship:

I was assigned once to an all-male team with a resident team leader… That resident contributed roughly 320 hours of misery to my life, including daily humiliation (he announced … that I was pregnant, that I had contracted HIV from a patient …); threats (he would drill me with questions no student could possibly answer … and would threaten to fail me and write a disparaging letter to my dean;… I was regularly assigned to noneducational tasks such as … giving him massages);… and sexual harassment (once, when our team went to the MRI room late at night, he announced that this was where he liked to rape medical students).20

In Ms. A’s case, the sexually based conduct of her supervising resident appears even more offensive in light of his role and responsibility to evaluate her as a student, possibly giving rise to a quid pro quo sexual harassment claim.20 In many training programs, the role of a supervising resident as an evaluator of medical students is very important, perhaps carrying more weight than an end-of-term examination. Conduct interfering with educational opportunities would more likely give rise to a hostile environment claim, even in the absence of a resident’s power to give a negative evaluation.

Ms. A reported the resident’s behavior to her clerkship director, but little action was taken.20 Although Ms. A chose not to file a lawsuit, a medical school might also be liable for its environment independent of the individual student. If a subsequent student files a sexual harassment claim, the court or the OCR might consider Ms. A’s case as prior notification of a hostile environment at the medical school. The school might also then face the loss of federal funding if it were decided that the school had knowledge but failed to take legally appropriate steps to correct such an environment.

Many medical schools may arguably have been put on notice of the possibility of a hostile environment at their institution. Deans have received reports from the AAMC survey with specific information related to sexual harassment at their own institutions. The survey asks students to indicate the frequency of different types of mistreatment, including being “subjected to unwanted sexual advances by school personnel” and being “subjected to offensive sexist remarks directed at you personally.”13 Unless the school’s report is scored a “0” on such questions, the AAMC survey results confirm some level of sexual harassment and a less-than-ideal learning environment. This scenario could be viewed as constructive notice of a hostile environment. Under the OCR regulations, the deans’ knowledge may give rise to a duty to inquire and take action against sex-based discrimination at their respective medical schools.

Constructive Approaches a Medical School Can Take

According to the OCR, schools must take proactive steps to deal with or effectively ward off sexual harassment within their medical education programs. Far more than just the school’s bottom line is at stake. Everything—from its credibility, public perception, and the quality of its programs, to its teaching affiliations and its ability to recruit the best and brightest future doctors—is tarnished by both private payouts and the public relations nightmare of sanctions from a supervisory body. Ideally, medical school administrators should aim for genuine compliance; their goal should be to both stamp out the bad behavior and to foster good behavior. The following discussion describes constructive approaches a medical school can undertake.

Assess the Environment

Every school must look closely at the environment it provides to its students. Is the environment conducive to learning, or is it hostile to select individuals? Several assessment resources will aid in the environmental review:

- AAMC Survey Results. These results are a good first-line indicator of a harassment problem within the program.

- School-Based Environment Survey. Schools should initiate their own information-gathering vehicles to better understand the specific issues in their program. Because students rarely report their negative experiences to authorities,12 deans cannot wait for the students to come forward, but should use regular surveys, focus groups, and formal course evaluations to solicit information about the learning environment. If a medical school conducts seminars, workshops, and lectures about sexual mistreatment for faculty and students, then the school should utilize an anonymous survey of the participants in these events to provide continuous information about mistreatment issues within the program. A mandatory annual survey of all clerkship coordinators and other faculty could be used to assess their understanding of appropriate behavior in the educational environment and their familiarity with the medical school’s policy on mistreatment. Formal course evaluations should also be designed to include an assessment of mistreatment. For example, these evaluations might include a question such as “Did the professor/supervisor make offensive sexual remarks, either publicly in class or to students privately?”

Establish System for Notification and Response

As indicated by the previous discussion of Supreme Court findings, liability for monetary damages may depend upon the school’s response to actual notice of alleged harassment. The school may receive notice in several different ways:

- The student might file a grievance with an appropriate administrator or complain to a teacher.

- Another student or individual might contact appropriate personnel on the student’s behalf or out of his or her own concern.

- An agent or responsible employee of the educational institution might witness the harassment.

- Notice may come to the university through indirect means, such as the campus newspaper, the local media, or through flyers posted around the school.

Even if the student fails to use the school’s formal procedures, the school may be in violation of Title IX if it has actual notice and fails to act.

When the school has actual notice of a potential violation of Title IX, the school is responsible for explaining grievance procedures and other dispute resolution procedures to the student. If the school directly observes the incident, the school should contact the student and explain that the school is responsible for taking appropriate steps to correct the harassment. There must be a prompt, thorough, and impartial inquiry. Occasionally, interim measures, such as the suspension of the harasser or a reassignment of students, may be required.21 Schools also have an affirmative responsibility to attempt to eliminate any elements of a hostile environment by providing services to the student who was harassed, and to prevent further harassment of both that student and others.

Further, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education has an accreditation standard that requires medical schools to define standards of conduct for teacher–learner relationships. It requires schools to develop procedures that allow medical students to report violations without fear of retaliation, using specific mechanisms for prompt handling of complaints and educational methods aimed at preventing student mistreatment.22

Such standards, had they been in place, might have helped Ms. A. She states:

In retrospect, I don’t understand why I didn’t report this earlier. I wasn’t worried about being believed, since there were so many witnesses … and so many people encouraging me to come forward. I kept remembering the words of the clerkship director during an orientation talk …, “Nobody likes complainers,” he said. When I finally did come forward at the end of the rotation … . very little action was taken.20

Apply Educational Interventions

Schools must educate all constituencies, including their administrators, staff, and students, about the concept of sexual harassment and its remedies and actions to discourage or prevent harassing behavior. In addition to decreasing the incidence of sexual harassment, educational initiatives should aim to respond in a timely fashion to victims of sexual harassment and, where appropriate, provide resources or standards to judge whether or not an offender is rehabilitated. For example:

- Educational initiatives should be addressed to students, residents, faculty, and the administration.23

- Outreach efforts should be made to educate clinical faculty in the hospitals, as well as housestaff.

- Clerkship coordinators should receive specialized training in recognizing and dealing with sexual harassment issues.

- Educational and behavioral initiatives might include the development of educational programs for students that define and discuss issues of abuse, discrimination, and harassment. These sessions might occur simultaneously with entrance into the clinical years of training, and annually in residency training.

- Evaluations of trainees, faculty, and housestaff should include assessments of harassing behaviors.

- Other methods that can bring reporting mechanisms to light include running ads or writing columns in student newspapers, and adding questions on the evaluation forms through which students report on their learning experiences.

Toby Simon and Cathy Harris24 developed a peer education training program for undergraduate students because they found that “there are some issues where peers, rather than professional staff, can do a much better job educating students.” An initial session, called “The Sexual Abuse Circle,” devotes 30 minutes to a discussion helping students identify and define the elements of sexual abuse and distinguish between abuse and harassment. Another exercise, entitled “Talking about Sexual Assault,” utilizes small groups of students to discuss their discomfort with talking about intimate things like sex. The goal of the latter exercise is to teach communication skills that can then help students recognize and reduce the likelihood of sexual abuse and assault and enhance their ability to communicate with patients in the future.

An experiential program at Brown Medical School involved residents in the production of educational videotapes on the mistreatment of medical students. The program utilized residents to role-play scenarios that portrayed events of medical student mistreatment. Following the program, residents reported that they had benefited from an increased awareness of the effects of student mistreatment and had learned how to handle mistreatment more effectively. The residents who participated in the program stated, “that their increased sensitivity and ability to identify and resolve issues of mistreatment would help reduce medical student mistreatment in the future.”25

Medical schools can adapt such exercises to their own educational initiatives. Through group discussion, teaching, handouts, and supervision, the schools can educate and inform their faculty, residents, and students clearly as to behaviors that are acceptable and those that are not. The Faculty of Medicine of the University of Toronto developed a half-day curriculum, consisting of lectures and workshops, to educate medical students, residents, fellows, and faculty on issues related to teacher–learner mistreatment and harassment. In an evaluation following the program, 54% of the faculty participants stated that they were likely to change their clinical or teaching practices as a result of the training.26 In a separate study at the University of Toronto, Moscarello et al.27 found that faculty education on sexual harassment and discrimination resulted in a moderate decline in medical students’ experiences of noncontact sexual harassment over a three-year period.

The school should take an active role in promoting contemporary and inclusive language. It should regularly supply material to all appropriate supervisors; make sure the supervisors know and understand the material; and make clear the desired outcome—the elimination of inappropriate behaviors. There should also be a formal means of identifying and addressing the inappropriate use of sexist teaching materials and sexist jokes. The school should be assertive in labeling and addressing discriminatory and abusive events and publicizing the steps it has taken in addressing these issues.

Finally, from its environment assessment and education initiatives, a school should be able to construct a policy, and indeed a primer, on unacceptable behaviors. The sexual harassment policy should set forth the school’s expectations for all levels of personnel within the program, and ensure that all program participants are operating from the same set of standards. Part of the program should include a formal evaluation of the effectiveness of the educational interventions. Surveys of the environment, such as those described in the prior section, should be done on a regular basis. The commonly used performance improvement system of Plan, Do, Check, Act (PDCA) might be used as a model to assess the effectiveness of any intervention. The AAMC Group on Student Affairs published a compendium that addresses the process of developing a school policy on student mistreatment and presents illustrative educational programs used to prevent student abuse at a variety of medical schools.28

Create a Structure

Schools are required by the OCR to adopt, publish, and disseminate grievance procedures designed to provide early notification of problems.3 Such procedures should be openly published in school publications or a student handbook. Requiring each student to acknowledge receipt of the statement of grievance procedures and policy may actively promote heightened awareness.

Appointing an ombudsperson outside the scope of official administration may add a level of confidentiality and objectivity, and a greater degree of comfort that retaliatory behaviors will not occur. A confidential advisor may provide background information and inform potential complainants of their options for addressing their concerns. The ombudsperson may also serve as the collective memory of the institution by maintaining an informal record to identify repeat offenders. Students who have declined to complain officially may choose to come forward more willingly if there are several complaints against an alleged offender. At one school, several students came forward with complaints of sexual harassment by a professor after it became public that the same professor sexually harassed another student.29 Ms. A feared that she would be seen as a complainer if she reported her experiences of sexual harassment to her clerkship director.20 The use of an ombudsperson may help students like Ms. A who need support but fear stigmatization. Additionally, the ombudsperson can serve as a referral source for support groups that might be useful in helping students address sexual harassment problems.

Separate structural initiatives might be required for students and residents in affiliated “off-campus” placements. A full corporate policy and formal affiliation agreement should address sexual harassment and hostile environments in such placements, the steps available for students to initiate a complaint and, most importantly, the levels of responsibility (and potential liability) of both the university and the affiliated hospitals.

A formal process of evaluation is integral to the effectiveness and success of a structural initiatives program. In addition to the aforementioned environmental surveys, medical schools should require the ombudsperson to file an annual report on the incidence of reported mistreatment at the medical school. This report could provide an assessment of the effectiveness of the current program and communicate recommendations for improvement if necessary.

“Consensual” Faculty–Student Relationships

Every school should establish a clear corporate policy that prohibits consensual noneducational relationships between supervisors and trainees. Such a policy should suggest that no teacher–student relationship be entered into, at a minimum, because:

- Relationships that may appear to be consensual may not be so because of the inherent power differential between the faculty member and the student.

- A trainee who engages in such a relationship puts himself/herself in a position to be harmed.

- Disruption can and will occur in an educational environment in which one student is treated differently. There are important implications for fairness, especially within the medical learning environment, because of the apprenticeship model of clinical instruction.

- Even if a university maintains a strict position of ethical boundaries between teachers and their current students, the acceptance of any noneducational relationship between any student and a teacher may, at a minimum, cast doubt on the vitality of the university’s ethical commitment.

- Applying a fiduciary concept to supervisory relationships, all interactions between a supervisor and a student should be for the educational benefit of the student.

One medical school has taken a strong step in issuing a “zero tolerance approach” to faculty for any behavior, even consensual behavior, that can be construed as sexual harassment.30 Zero tolerance has many definitions, from prohibiting any relationship between a faculty member and a student while the student is in the program, to losing one’s job for a first offense of sexual harassment of any kind. A fiduciary relationship may be defined as existing between any student and any faculty member for the duration of the student’s enrollment in the institution. School policy must clearly state the limits of the boundary of faculty–student relationships.

Not all schools may choose to have a zero-tolerance policy. If a teacher does enter into a relationship with a student, then the school’s policy must emphasize that such behavior is disfavored, and that in the event of a complaint, it will be presumed that the relationship was not consensual. In compliance with the due process rights of an employee or agent, the policy should set forth the standard and process to challenge the presumption. The standard for review might indicate that the presumption could be overcome only by clear and convincing evidence as to the consensual nature of the relationship. Such a policy addresses the due process rights of employees or agents by putting them on notice and conditioning their employment agreement on their consent to the policy. The policy also protects students by discouraging faculty from pursuing such relationships and by providing procedural protection in any complaint hearings that may be held.

A Proactive Response

Legally, under Title IX, medical schools and their officers are required to provide equal access to educational experiences without regard to gender. Educationally, medical training programs have a responsibility to provide a quality educational atmosphere free of sexual harassment. In light of the current medical literature and AAMC surveys, medical schools have been duly informed as to the presence of sexual harassment generally and specifically in their training programs. Thus, the proactive response of medical schools to sexual harassment might be threefold:

- Ensure appropriate notice procedures.

- Encourage appropriate reporting.

- Create procedures for taking appropriate corrective action.

To shield itself from liability when sexual harassment occurs, the school should have four goals:

- To ensure protection of the victim.

- To rehabilitate the offender if possible.

- To minimize the likelihood of recurrence.

- To establish appropriate standards for the future practice of medicine.

All of these policies and structures are meant to minimize, or rid the environment altogether, of the occurrence of sexual harassment. The ultimate goal of the medical student’s education is to become a doctor and treat patients. Any impediment to any student’s learning within the clinical setting may make their treatment of patients—both present and future—less effective. Ms. A put her personal spin on the impact of sexual harassment on medical education:

Why do we spend so much time on issues like student abuse and resident working conditions? I believe that there is a direct connection between hospitals’ inhumane working conditions and the lack of compassionate care experienced by many patients.20

Ms. A’s reflections highlight the direct effects that sexual harassment may have not only on one trainee, but also on the entire educational environment, subsequent relationships with patients, and the medical profession as a whole.